From Oppression to Expression: A Journey of Art and Liberation. Interview with Tasleem Mulhall, British-Yemeni Artist Living in the UK

How does your background, growing up in Yemen and later coming to England, influence your artwork and perspective on freedom?

Being born in South Yemen and experiencing life under communism, then dictatorship and Sharia law definitely left its mark on me. Even though I was quite young at the time and didn’t fully grasp the political nuances, I remember the pervasive atmosphere of fear and censorship. Despite this, one aspect I appreciated under the communist system was the relative freedom for girls and women compared to later periods under dictatorship. During the communist times, I participated in school activities, such as sports – I loved running – and theatre, where boys and girls were not segregated. However, as Yemen transitioned into a dictatorship, those freedoms were curtailed, and life became more restrictive, particularly for girls like me who dared to challenge societal norms.

Since I can remember as a child, I’ve always had a desire to create. I believe I was an artist from the very beginning, constantly crafting and building up sculptures from whatever materials I could find, or painting in sand using water. I was often punished for that. I was being told that art was the devil’s work (in Arabic: Shaitan) and that, as a girl, I should behave differently. My family, particularly my mother, often questioned why I wasn’t conforming to traditional gender roles: “Who will marry you?” – she used to cry. I remember being labelled a rebel for speaking out against injustices, especially those directed at girls simply because of their gender.

I was a bit of a tomboy, never really dressed in a feminine way. I always preferred to stick with the boys, hanging out with my two brothers, roaming different neighbourhoods, getting into fights. I was part of a gang, the only girl among the boys, and we’d go around roughhousing or building things. I remember these makeshift toys we used to create from empty powdered milk cans. I couldn’t wait for my mom to finish the milk so I could get my hands on the can to build little cars or carts. There’s this one incident that sticks in my memory: a woman brought her son to complain to my mother, questioning what kind of girl I was for beating up the poor boy. I stood there hiding behind my mother, looking at the little snitch, and I distinctly remember making this gesture of hitting my fist into my palm, to show him I’m not finished with him.

Sometimes I’d even ask my mom, “Can I get my advanced beating?” She’d say, “What nonsense are you talking about?” And I’d reply, “Well, just in case I mess up again”. So yeah, I think growing up in Yemen taught me to stand up for freedom and face whatever punishment came my way. I find it’s particularly the culture, tradition, and religion into which I was born that wants to make me feel somewhat hopeless. It aims to protect me, but paradoxically, it harms me. It tends to silence my voice, stripping away my rights.

From an early age my family in Yemen was already arranging my marriage, dictating my future and what I was expected to become. Today I’m a mother of four, and I’m incredibly happy and proud of it. But I can’t help but think, being a wife or a mother doesn’t define me entirely; I am so much more. I’m fortunate to live in the UK, where I have the opportunity to express myself freely. However, there are still certain topics that I’ve been silenced on here, experienced injustice and missed opportunities simply because I spoke up.

What challenges have you faced as a first British Yemeni female artist breaking into the international scene, and how do you hope to inspire other Yemeni girls through your journey?

I may be the first Yemeni to get international recognition, but I certainly don’t want to be the last. I aspire for other Yemeni girls to follow their dreams. Given the challenges we face, I understand the significance of Islamic indoctrination on our development. Growing up without prominent role models, I learned to forge my own path, becoming the beacon I wished to see in the world. If my journey can inspire even a single individual to amplify their voice and transcend their comfort zone, then I consider my mission accomplished.

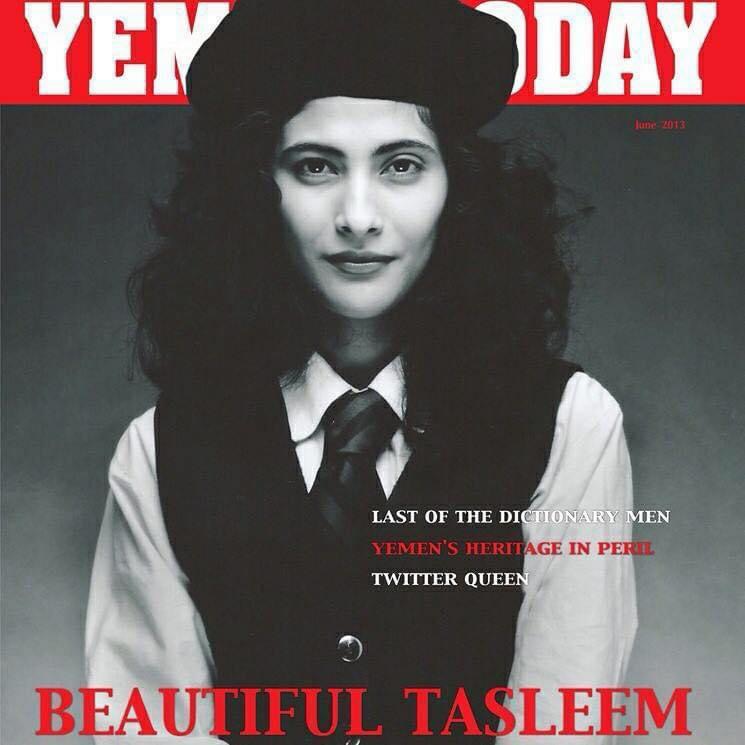

Interestingly, my niece recently sent me a message saying, “I see you all the time on my TikTok feed,” along with a TikTok featuring my photograph on the cover of Yemen Today. Although the photo was taken years ago, it continues to circulate virally on TikTok, depicting me as one of the most influential Yemeni women. It’s quite an honour for me.

I planned to exhibit at the Yemeni embassy in the UK. Unfortunately, each time I try to arrange it, some conflict erupts in Yemen, and it’s never a good time. It’s disheartening because I aim to spotlight the positive aspects of Yemen and its culture, which also holds immense beauty. I take great pride in my heritage and background; there’s much to appreciate. I strive to embrace and celebrate it. I’m proud to be British Yemeni.

Your work often addresses themes of oppression and injustice faced by women in male-dominated societies. Do you see art as a tool for challenging societal norms and advocating for freedom?

I don’t sit down and ponder who I might piss off next. My art is always authentic. I’ve gone through a lot in my life – the threat of honour killing, domestic violence, you name it. I’ve experienced it all. However, I’ve also found that art is healing. Art has given me a voice, it’s given me confidence, and it’s given me an identity, allowing me to speak up freely without fear.

I channel my own experiences into my work, allowing art to speak for itself. It has a way of conveying truths without words; it just tells you. I simply follow the truth and remain honest in what I create. I know my art can be quite confrontational at times, but it’s powerful, because through my artwork I reveal my vulnerabilities.

I’ve always gravitated towards taboo subjects in my artwork. Topics that were considered off-limits, things people didn’t want to talk about. Some would even say I was airing my dirty laundry in public. It took a lot of courage for me to open up about what I’ve been through. It took years to muster the strength to talk about it, to release it from my system, and to feel secure and liberated enough to express it through my artwork. And I paid a big price. I made a lot of sacrifices, and my own family rejected me. But as an artist, I feel that through my art, I can be the voice for other women and girls who haven’t had the opportunity to speak up, who are suffering in silence. I see it as my obligation. My experience is an opportunity to shed light on issues such as honor killings, FGM, forced marriage, child marriage, domestic violence. Some time ago I always used to worry about what my parents and my children would think. But as an artist, I’ve realised that I can’t let that hold me back. I have to delve deep into my soul, embracing my vulnerability and my essence as a human being, as a woman. It’s this deep exploration that allows me to express myself authentically. If I were to hold back out of fear of upsetting my parents or anyone else, I wouldn’t be doing justice to myself, or my creativity. I’d also be neglecting the women who are often forgotten. As an artist and as a woman, I feel compelled to create things that feel right, that are true, and that reflect the reality of what women are going through. Because being a woman in this culture, tradition, and religion, is like being trapped in invisible chains. Therefore I have to be true to myself, despite how emotionally, physically, and financially challenging it may be. I have to let go of all those constraints and focus on the why behind what I’m doing and whose voices I’m trying to amplify or issues I’m trying to highlight through my art. I perceive it as a moral obligation to remain steadfast in expressing my truths, irrespective of concerns regarding sales or potential backlash. To compromise on this would betray not only my creativity but also my core identity. I persist in my commitment to authenticity, even amidst the most arduous circumstances, viewing it as an opportunity to advocate not just for women in my homeland but for women globally. Despite the myriad challenges we encounter, there is the potential for transformative change, for the revelation of truth, and for meaningful action.

As artists, we may feel invisible in society, but we have the power to shine a light on what’s happening around us, to reflect the experiences of those who may not have a voice. That’s why it’s crucial to remain true to ourselves and to fearlessly express our truths. But it’s not only a sense of duty, it’s also a privilege and a gift.

Your diverse range of mediums, from photography to sculpture, reflects the complexity of the issues you address in your artwork. How do you decide which medium to use for expressing a particular message or idea?

Thankfully, I never went to art school. When I applied to art colleges and was rejected, I thought it was a tragedy, but now I see it as a blessing. Because I haven’t been confined to a specific mould or way of doing things. For me, being an artist and a creative person means being free from restrictions, experimenting, and allowing creativity to flow like a river, leading me wherever it may go.

I initially started creating art in my bedroom. My debut sculpture, “People’s Angel,” was crafted from over three thousand wine corks, resulting in my bedroom smelling like a brewery or a pub. In 2009, I moved to the Redlees Studio, which I was often sharing with artist friends. And one of them watching me work once told me that I have a personality disorder, because I cannot stick to one form of art. But for me, it’s more like a light bulb moment. When something affects me or triggers a memory I’ve repressed, it’s like a switch flips, and I know which medium to use to express it. That’s the beauty of art. I’m not a factory; I’m creative. Recently, someone suggested I should make five items in one thing to increase sales. But that’s not my approach. I don’t ponder, “How can I churn out items just to sell them?” It’s not my style. I don’t create with profit or controversy in mind; instead, I focus on the idea and the emotion behind it. I use whatever medium necessary to express myself authentically. I visualise my ideas in three dimensions in my mind—a meticulous process that can take weeks or months to refine. Each idea feels like my child, and I’m fiercely protective of my work. My art reflects what I’ve experienced, how I’ve changed, and how I’m growing from a girl to a woman. It’s about allowing emotions to come out and having the freedom to release them. Art has been incredibly healing for me. It saved my life.

Your sculptures and paintings evoke powerful emotions and convey profound messages about freedom and liberation. Could you share with us the story behind a particular piece that holds special significance to you in this context?

I am a self-taught artist, and it all began after my marriage fell apart. I married my rescuer, who later became my abuser. In my culture and family, divorce is heavily stigmatised. Escaping the abusive marriage proved more difficult than hiding from the threat of honour killing for over a year. So, when I was going through divorce, I had this overwhelming emotion that sparked something within me. It ignited a desire within me to pursue art further. Earlier on I used to believe that you needed formal education, like attending college or university, to be considered an artist. But now I realise that if you wake up and go to bed with the urge to create, you’re an artist. It doesn’t matter what form it takes—whether it’s writing, poetry, painting, photography, or anything else. That creative impulse, that relentless feeling urging you to express yourself, you just have to let it out. Whenever something dramatic happened, painting was my outlet. My first paintings were about losing a child and trying to leave my ex-husband for the first time. These experiences gave birth to ‘’Jamila’’—my first self-portrait.

When I was young, I was often called by various nicknames. One of them was “Ati Al Sawda,” which means the Black Swan, because I was different from the rest of my family. They even called me “Ahmed” because I was such a tomboy. Growing up, I didn’t feel pretty or feminine. So, ‘’Jamila’’, which means ‘’beautiful’’ in Arabic, became my first recognition of my femininity as my power. She represents the struggles of a young girl facing oppression. In Islamic culture, it’s forbidden to depict figures, but I painted Jamila naked—not for sexuality but to symbolise the liberation from the restrictions placed on women. Living in the UK, I learned an expression: “Children are to be seen but not heard.” In contrast, in Islam, women are often expected to neither be seen nor heard. Behind her stands a dark figure of a mullah, whom I remember from my childhood and who punished me for questioning him during religion lessons. ‘’Jamila’’ was my rebellion. She made me feel like I was reborn—as a person and as an artist.

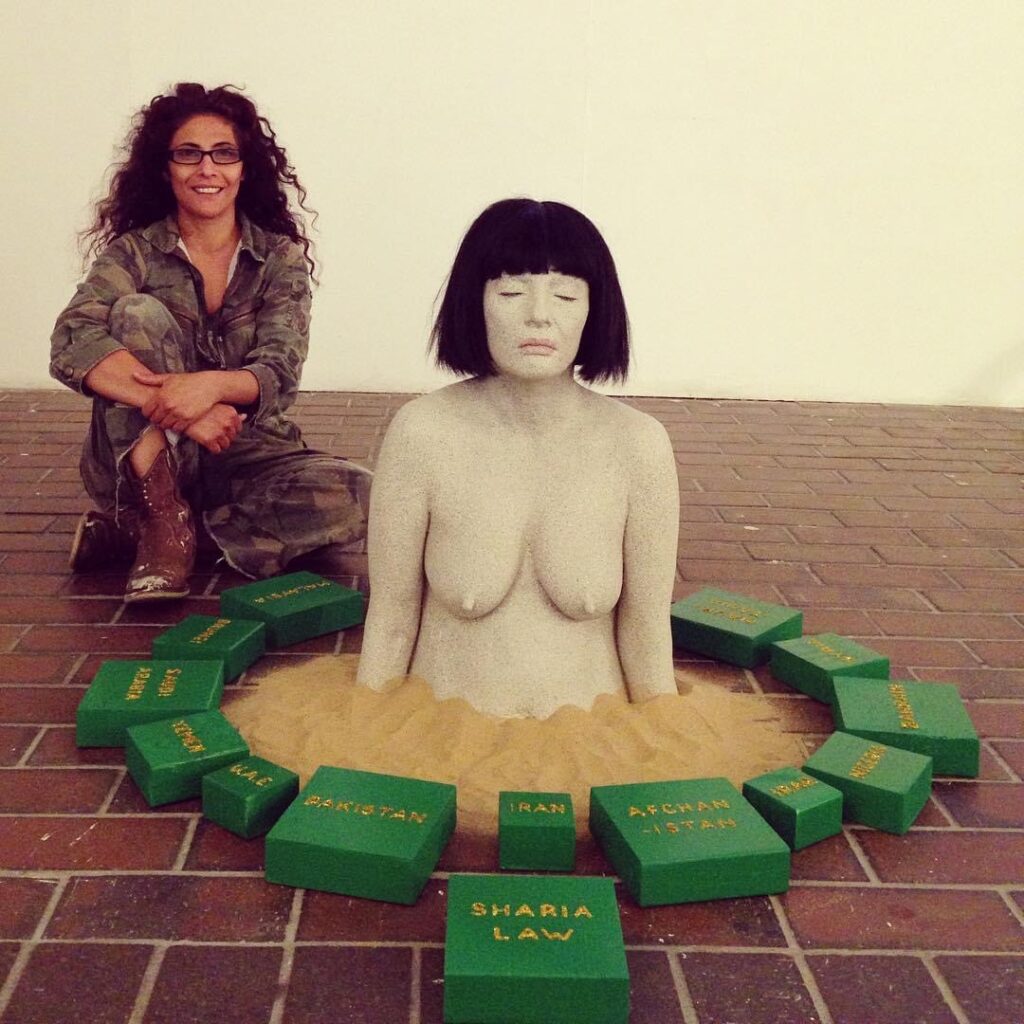

And then there’s “Stoned,” a sculpture that ignited considerable controversy during the 2015 Passion for Freedom exhibition at the Mall Gallery in London. Police intervention aimed to ban it, yet it eventually found its home in the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Poland. This piece holds immense significance for me, symbolising the grave consequences I would face if I were still in Yemen, where stoning remains a real and lethal punishment endured by many women in regions such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Creating “Stoned” was an incredibly emotional journey. As I posed naked for the sculpture, I couldn’t escape the weight of fear and uncertainty. It was a mixture of emotions: I let myself imagine what I would feel if I was captured there waiting for the first stone to hit my body. At the same time I was in the here and now, embracing the thoughts of my parents’ reactions, the vulnerability of baring myself, and concerns about my children flooding my mind. It felt like being buried alive, I was immobilised by sheer terror.

My dear friend Jamie, an exceptional artist and sculptor, assisted me in casting the sculpture since I couldn’t do it alone. I recall breaking down emotionally during the process, overwhelmed by the intensity of the moment. Despite the turmoil, creating “Stoned” proved a profoundly cathartic experience for me.

And then there’s “Silenced,” a photograph of me, naked, self-muzzling with a large knife, while surrounded by five women wearing burkas. Interestingly, those burkas belonged to my sisters-in-law. When I requested them to send me burkas, they assumed I had conformed to their cultural expectations, believing I had embraced a traditional Muslim identity. However, upon seeing the photograph, they stopped speaking to me for a long time.

This was yet another instance where I exposed my vulnerability, taking a significant risk. However, unlike before, this act came with a heavy price. I received death threats for that photograph.

Do you know who was behind these threats?

No. They were anonymous phone calls, messages on my social media accounts. I had to take down my website because it became a platform for harassing phone calls, violent emails, some even containing explicit and pornographic content. I was bombarded with all sorts of violent language, initially brushing it off as trivial. However, it soon escalated to a serious level. A close friend, who happened to be a police officer, sternly warned me, saying, ‘You have to take this seriously.’

I decided to seek help and approached my MP. Initially, the police investigation yielded little progress; they never traced the perpetrators. Consequently, I had to install a panic room in my house, complete with double locks on each floor. The threats were terrifying, especially considering my young children at the time. They mentioned gruesome acts, like cutting my throat and letting my blood flow like a river.

The threats persisted—threatening phone calls and three incidents of trespassing in my studio. I found myself repeatedly reporting these incidents to the police. Even now, I remain cautious about whom I interact with and where I go, as the perpetrators continue their attempts to intimidate and silence me.

I refuse to be silenced. I would rather die than live a single breath without freedom. I’ve encountered several threats to my life, both from within my own family and due to serious illnesses. I know I am going to die one day, we all will. For me, freedom is not a privilege but an essential human right—a fundamental ability to uphold one’s beliefs and advocate for others.

If I don’t stand up for those who are marginalised, for the countless women who have yet to attain the position I currently hold, then who will? I’ve walked in their shoes—I understand the profound sense of isolation, of being rendered voiceless and forsaken. It’s an experience I wouldn’t wish upon any woman, any girl, or any human being.

Could you share a bit about your inner and outer processes when creating art that challenges societal norms and promotes freedom? How do you balance the emotional demands of such work?

There’s a lot of crying involved. Many tears are shed during the creative process. Sometimes, I wonder how I still have friends with all the emotional intensity I go through. When I’m in the artistic zone, I feel like an artist possessed. The emotions are so intense that I have no control over them; I can’t just switch them off. It’s as if the urge to create is a relentless drive fueled by intense emotions. My work is inherently emotional and tense. I’ve cried countless times during various projects, questioning why I subject myself to such emotional turmoil. My son once asked me, “Mum, why don’t you just paint something uplifting instead of always choosing challenging subjects? Why can’t you just paint flowers?” And it made me ponder: ‘’exactly, why?!’’ But I embrace the challenge of these emotions rather than suppress them. Each artwork, sculpture, or medium I choose becomes a form of healing, not only for the inner child in me but also for the teenager and woman who have endured so much. It’s as if I’m providing them three with a voice, a means of release.I recognize that I am who I am because of these three parts of me: the child, the teenager, and the woman who have experienced so much. It’s about acknowledging the anger, the pain, and the disappointment and transforming the negative into something positive. So, I express gratitude to these parts of me who have endured so much, and to the woman I’ve become. Sometimes, I feel vulnerable, and a part of me gets scared that people will know everything about me. But if we don’t speak out, how can we change things? How can we make a difference if we don’t talk? We need to confront the difficulties, challenge them, and let the emotions out. Without doing so, there is no growth.

Your most recent sculpture “War Not Peace” offers a provocative commentary on the Israel-Palestine conflict. What inspired you to address it?

This sculpture was actually inspired by a visit to my mother’s house, where discussions about the conflict reignited. It’s intriguing because despite growing up in a culture with animosity towards Jewish people and Israel, I’ve always been drawn to Yemeni Jews and Jewish culture, even though I didn’t fully understand it. Some years ago I exhibited in Tel Aviv and explored Israel. When I visited Jerusalem and the Wailing Wall, I was in a phase of being quite anti-religious. Though, the experience I had there was emotionally profound. Later I wanted to visit the Dome of the Rock mosque. A young man at the entrance asked if I was Muslim, a label I’ve never fully embraced, usually getting a lot of beating for it from my father who always reminded me of the meaning of my name, Tasleem, which means “submission”. He still hopes I will convert back to Islam, but I would always answer him back: ‘’Dad, I didn’t submit to Islam in Yemen, I will not submit in the West.’’ So, when I visited Jerusalem and approached the Wailing Wall, nobody questioned my presence; I simply entered. Yet, when I attempted to visit the Dome of the Rock, I was met with an unexpected inquiry. The guard asked me, ‘Are you Muslim?’ Finding the question peculiar, I replied, ‘No, I am not.’ To my surprise, he denied me entry based on that response.

Later, discoveries from my DNA testing revealed my mixed ancestry, including genes signifying Yemeni Jewish and Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. My parents were hugely displeased, but this revelation made sense to me in regards to my affinity for Yemeni Jewish music and my interest in the historical migration of forty nine thousand Yemeni Jews to Israel, known as the “magic carpet.” I felt that my experience at the Wailing Wall was like my ancestors calling.

Isn’t it sad and ironic that most probably people on both sides of the conflict could find their enemy’s genes in their DNA.

That is why I personally feel so much empathy towards people trapped in the ongoing conflict between Palestine and Israel which has deep historical roots, spanning centuries. During a discussion with my mother about the conflict, she suggested donating to the Palestinian cause through charity, and I asked her: ”Do you think this is the solution? Do you know where the money is going?”

Because I spent over four months conducting thorough research, meticulously gathering documents from credible sources. I questioned where exactly the funds are being directed. From 2014 to 2020, UN agencies contributed nearly $4.5 billion in aid to the Gaza Strip’s two million residents. The US has provided over $5.2 billion in aid since 1994, while the EU has donated 2.2 billion euros between 2014 and 2020. Additionally, the UNRWA, dedicated to assisting Palestinian refugees, operates with a budget of $806 million. The US has contributed $130 billion of military funding to Israel since the country’s foundation. Where is all this money going? Now, the combined wealth of Hamas’s three leaders amounts to $11 billion, with a turnover of $1 billion. Benjamin Netanyahu possesses a net worth of $80 million.

There’s simply too much money to lose by peace.

I didn’t make this all up, but please do not just take my word for it. Go and check it all yourself, there are documents available for public view.

In my sculpture “War Not Peace,” I wanted to convey this perspective on the Israel-Palestine conflict. I believe that peace seems unattainable because it would disrupt the financial interests that fuel the ongoing strife. The centrepiece of the sculpture is a wheel, symbolising the perpetual cycle of conflict between Israel and Palestine, reminiscent of the tires Palestinians burn in protest. I describe it as a “wheel of fortune,” where financial gain comes at the expense of countless lives. The conflict persists due to the vested interests of various stakeholders, including politicians, charities, NGOs, weapons producers, and the media, who profit from its coverage. I want to emphasise how leadership exploits their own people for personal gain. I want to highlight the immense sums of aid and military funding involved, questioning where all this money truly goes. I want to challenge the narrative perpetuated by charities, revealing the complex web of interests at play. The more I dug, the clearer it became that both sides, along with their politicians, corporations, and governments, are exploiting the people. They’re profiting from conflict. In my sculpture, I incorporated slogans from both sides, which are found on the rockets. I obtained authentic Israeli and Palestinian rockets after a four-month wait. Every element in the sculpture is genuine. I poured countless hours into this project, often working late into the night in my home studio, sometimes until two o’clock in the morning. I even took on extra shifts, working tirelessly to afford the rockets. Do you know how much money I had to pay for these rockets? Just for four rockets I had to work double shifts for months. How many of these rockets killing innocent civilians were sponsored by people donating to charities?

Addressing this subject wasn’t easy. I understood the potential for backlash. Even my children expressed concern, warning me to be cautious. However, I am confident that this is a conversation that needs to be had. I aim to remain neutral. I’m not taking sides; I’m not anti-anyone. But there are glaring inconsistencies in the prolonged conflict, with vast sums of money pouring into both Palestine and Israel, yet the lives of the people remained stagnant, if not deteriorating. It is evident to me that the military complex profits immensely from this ongoing strife.

What specific actions or initiatives do you recommend for artists in Western countries to effectively advocate for freedom through their art?

I urge artists worldwide, especially those in the West, to recognize the voice they possess. Evoke emotions, spark conversations, and ignite dialogue, whether loved or hated. Use it for good, advocate for justice, and defend freedom because it’s fragile. Freedom is not something to take for granted; it requires constant vigilance because it can vanish in an instant. If we don’t stand up now and fight for what we believe in, freedom of speech and artistic expression, these powerful tools, could be lost. Artists bear the responsibility to advocate for freedom, not just for themselves, but for society and humanity as a whole. Protecting it is everyone’s responsibility. Freedom is essential as food or air… Throughout history, people have fought and died to defend it. This fight is particularly crucial in the West now, as losing freedom would leave us with nowhere to turn. We must save it, protect it, and be willing to fight for it, even to the death.

As an artist who has faced challenges and adversity, what advice would you give to aspiring artists who aim to use their creativity as a tool for social change and freedom?

Have no fear.

But how?

Surround yourself with people who are braver than you, people who believe in you even before you believe in yourself. Surround yourself with supportive individuals who understand your vision, even when your sketches or paintings may not be clear. I’ve been fortunate to have many such supporters in my life who saw potential in me that I couldn’t see in myself. Maintain a positive attitude, and whenever negativity arises, transform it into positivity. Dive deep into your emotions, confront your fears, challenge them, and this is how you will ultimately heal them.

It’s like a volcano erupting. When it does, the lava flows, and it’s hot and dangerous. But when it settles, it creates a stunning sight. It’s almost like a work of art. Like a volcano, let your ideas build up and then erupt, allowing them to flow freely like a river. Nurture your ideas slowly, be curious, and believe in your ideals from within. Remember, you don’t need external validation to believe in your work; it must come from within. Embrace your uniqueness and eccentricity, and never let fear hold you back. Challenge yourself, grow, and allow your creativity to flourish. Be passionate and determined even if it means working tirelessly day and night to pursue your dreams. Be unapologetically yourself and lead by example.

Get up from that bloody chair and go, create! I don’t care what you choose to do. Paint flowers!

Author: Sara Komaiszko